I’m flying home. I look out from my porthole at a white, grainy sea. It churns cyclically. My gaze rests unfocused on hundreds of wind turbines, sedated by the Bardo of travel and the low hum of a three thousand pound jet engine. A light trip. A trick of the eye. Sleep playing across the face.

Some part of me has slipped into an altered state. 30,000 feet in the air, despite the best efforts of a plastic, WiFi-enabled ship, the membrane separating my own world and the next has thinned. It is affecting me. The watertight seal leaks a slow, steady, drip. Beads of condensation slide up the window. I see myself looking past them. There are things on the other side of the glass. Industry and sky.

The sky is often used as a metaphor for the mind in traditional Buddhist teachings. Skygazing itself is tied to the Dzogchen cultivation of awakening. The practice, thod rgal, can be translated literally to “Skullward Leap.” To look to the sky is to look beyond oneself. To look to the sky is also to look inwards. The polished window of an aircraft is a mirror.

The Bardo is a Buddhist transitional state. It exists between places, across planes. The Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, describes it as somewhere between life and death. I see the Bardo all around me. In travel, we live out miniature lives followed by miniature deaths. We traverse spiritual terrain and return changed. It is clear to me that there’s something more to this world in the sky.

It’s my first summer back home and arid Eastern Washington sprawls beneath me infinitely. Now I think to myself that the turbines look like tombs, scattered into the blurry distance. A sandy desert graveyard. A burial at sea. My eyes close and I gaze into a dark horizon beyond all of it. I am listening to Music For Airports and having a moment. It’s the soundtrack to the Bardo.

The act of flying is not meant to be so sacred. Barring a few quick words to a higher power brought about by a too-big bump or sudden drop in elevation, air travel is more often than not a spiritually dismal experience. Look around at an airport or on an airplane and you’ll see the exhaustive lengths to which your fellow pilgrims will go to distract themselves from the fact that they are at an airport or on an airplane. This is dissociation holy ground. Tired families pacify little ones with touchscreens over layovers, and homecoming locals with neck pillows and noise cancelling headphones sleepwalk to their terminals, the routine committed to muscle memory. It is as though the whole process is just a bad dream.

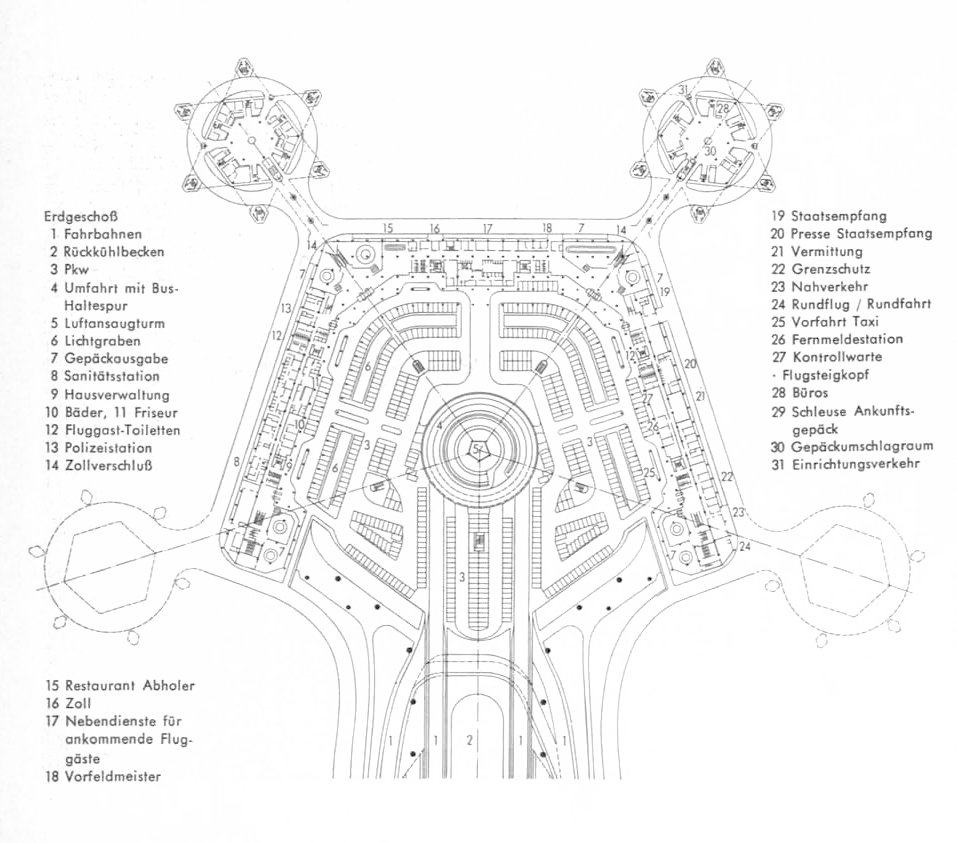

This is because the airport is the world’s ugliest Bardo. The differences between Torii and terminal gates are severe. Like comparing mosques to malls. Repeating gray halls of industry, soaked at all hours in fluorescent light, create one internationally continuous space, independent of their place on Earth. A dispirit realm, soundtracked by empty pop muzak.

It wasn’t always this way. In the early days of commercial aviation, flying was a luxury experience. Passengers dined in lounges, stewardesses wore couture uniforms, airports were shining new gateways to the sky. Then, as flying became cheaper, its glamour began to fade. In 1977, Brian Eno heard this change around him.

He recorded Ambient 1: Music For Airports in response.

Listen to Eno’s transcendent declaration of the ambient genre and hear a bright future. Hands meeting piano keys echoing like footsteps on marble, and voices joined, without speaking. An upraised, interconnected yet open globe with beautiful music beyond language. A utopia, because it isn’t ugly. For all its pained associations, the Bardo is a neutral space. An ambivalent force that curls and crests. Buoyed by Music for Airports, the emotion it stirs is awe.

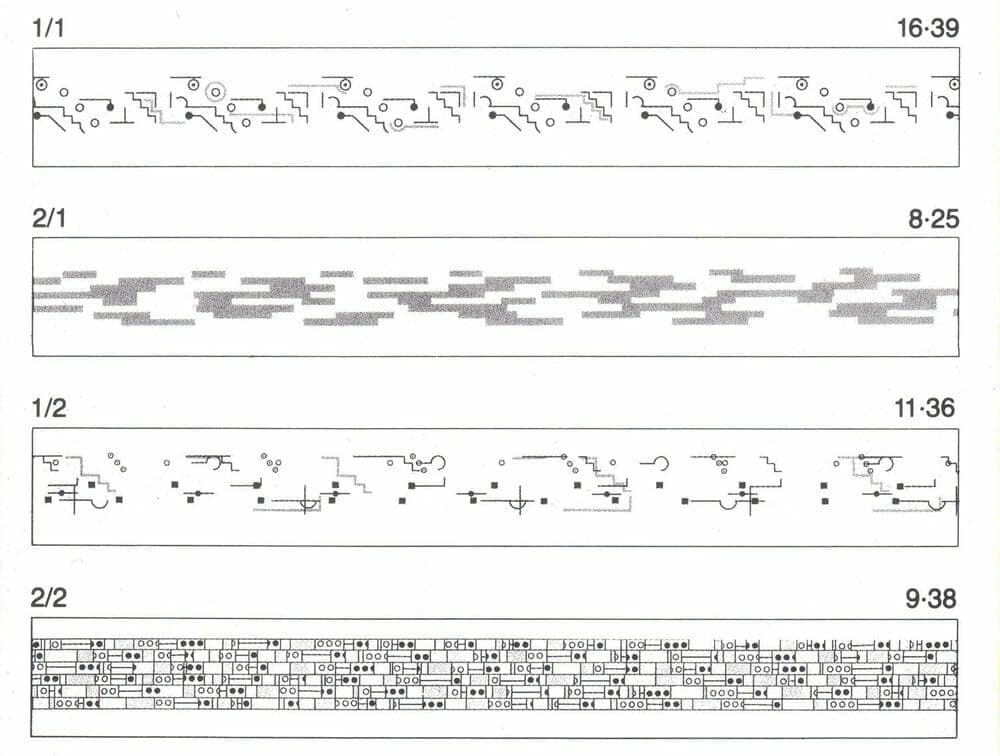

A sense of vastness permeates Music for Airports. One can imagine the album continuing on forever, past the bounds of its four diffusive tracks. In fact, each layered, offset loop could be stretched infinitely, independently, without the full composition ever repeating itself.* Within Music for Airports is a perfect architecture. Within airports, Eno found metaphors and art.

This trip feels endless. The plane’s shadow scales the topography below, on its own parallel journey. Inside, the graying woman taking up both seats in front of me keeps replying to the captain speaking over the intercom. She yawns gratuitously. I can hear her over Music for Airports. There is no one traveling in the seat next to me, either. I scrunch up with my back against the window and write.

I realize now that I sort of miss the San Francisco International Airport. That place has a lot of new age-y art. I read somewhere that they had to design their own meditation symbol for the yoga rooms, because it didn’t exist yet. A little stick figure Buddha. I’ll see it again soon.

The Bardo is arrivals and departures. You touch down with a little residue on you still. I write about the world that rushes in to meet me as I come out the other side. It is a world that is ugly. It is a world that smells. It is a world that is graying. It is a world leaving the finer things behind. It is the world I am from. At least, it is the world in which I live, with all of its light and space and boredom and spirit.

At least you can always throw on “1/2", close your eyes, and never have left. Always leaving. Always arriving. The soundtrack to a world just a trip away.

This essay was published in Humble Pie, CCA's art and literature magazine.

Works referenced and further reading...

Ambient 1: Music For Airports

Music For Airports liner notes

Generative Music

Generative Music transcript

Bardo Thodol

The Four Mind Changing Reflections

The Journey

Sleeping In Airports

*This isn’t really true, although Brian Eno wants us to think it is. The system of tape recorders and chairs that forms track 2/1, for example, if played continuously, would eventually repeat itself after almost 27 days (as calculated in Introduction to Generative Music). The way this generative music is made is really interesting and existentially slapstick, if you’re into that.