The more I write about music, the more I realize all I’m doing is coming up with new ways to describe the view from the present moment, soundtracked. In fact, when I sit down to write, this is usually what I really end up doing: looking out the window absentmindedly, listening to music. I’m not particularly thrilled that this is my process, but it just seems to be what kind of writer I am. You could call it my default mode network.

Studying my behavior, one could observe that, ultimately, I’m still a teenager, looking out from my bedroom window longingly, imagining my life’s a music video. Due to budgeting reasons, I have to be content with these moments being essays.

Another trope I’m discovering to be true: The narrator who, upon hearing a special song, is suddenly, melancholically, transported back in time to the exact moment he first heard it. I’m talking total Norwegian Wood, rainy airplane window and everything. It’s been happening so much to me lately it’s gotten to be disorienting.

Part of me worries that my life has been constructed entirely of derivative, media-induced narrative devices since birth.

All of this is why, headphones in, looking out the window of a bus, rolling along somewhere in Northern California, hearing Ryuichi Sakamoto’s “DOLPHINS” yanks me across spacetime. Just a moment ago, I’d been listening to a Japanese city pop compilation album, idly watching as Eurekas and Buttes flew by. “I was laced,” I think. That’s how strong the sensation is.

The track has this immediacy to it that moves you. Anticipation builds over a reverse reverb that just arrives. This is the oldest piece of music I’ve heard that does this, but it’ll always sound like the future to me. As always, we’re just now catching up to Ryuichi Sakamoto.1

It all shimmers, the digital keeps intact an analog warmth that sounds like sunshine hitting cold water. It must be the self-sabotaging part of me that keeps trying to put these things into words.

The aural wormhole deposits me onto a fall park bench, during my first week or two at art school in San Francisco, where I first heard this song. “Wow,” I say to my new friend, who’s playing it for me. We’re looking out at the house boats along the Mission Creek, with our backs to the skyscraping skyline across the street. It’s a weird city. We’ll live there together for two years, and get this album on vinyl in the spring.

He says he’s moving to New York, in the future, and I think of the similarly off–color Gowanus Canal in my old neighborhood, where we used to go to see all manner of dead things, washed out from who knew where, which occasionally were dolphins.2

I tell him I don’t know where I want to end up, which is misleading, under the assumption I’d want to end up anywhere for too long. We talk of his childhood in Tennessee, and my own, stretched across America, and how we both travelled to Japan in our headphones.

There’s something to Japan, to me, that feels the way I imagine Hollywood feels to people who’ve never seen the real walk of fame, or New York City to those still excited to visit Times Square. Ask most young people about their travel bucket list, and you’ll doubtless hear lots of stray Japanese: Cherry blossoms–Sakura, the sound of cicadas–semi, Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka…3 If, growing up in and out of the city, New York felt like the center of the universe, Japan always felt like the furthest corner, closest to the realm of imagination.

The first albums that moved me to write about them were Japanese.4

Pico Iyer, perhaps the travel writer, on first setting foot in Japan, wrote:

We’re not the first wandering men to connect Japan to an imagined, Eastern sublime.5 The shared sentiment’s gone by many names: Japonisme, Japanophilia… shinnichi. I think it truly started for me when I found a purple GameCube on the sidewalk at age ten, in Brooklyn. It was intact, with controllers and everything, but it might as well have fallen from outer space. I played the first few minutes of the scratched Zelda disc that was inside it over and over, and it left an impression. It was a videogame that was older than me, an artifact from someplace far, far, away from my life, and everything in it.

This continued into my standardly lonely adolescence, when, reading Haruki Murakami, I found I could feel exactly like any one of his nameless, interchangeable male protagonists, wandering, wearing headphones. However, by some mechanism the sensory association had been inverted, and instead of his boys’ American classic rock, I took up their mantle listening to Japanese ambient music. I do believe there’s nowhere I feel more deeply rooted, that I’ve never been to. Perhaps a person feeling isolated from the world around them is predisposed to believe in the existence of another, better one, far, far away. Another familiar, if somewhat ugly, trope.6

Murakami acknowledges that us English fans tend to miss the distinct Americanness of his trademark style. “Americans are different,” Murakami says. “Americans are strange because they don’t believe that we have Dunkin’ Donuts or McDonald’s or Levi’s or Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen in Japan.” Or, to some degree, young men who feel just as bad as they do.

In the years that follow all this, returning to the Gowanus Canal, I’ll think of “DOLPHINS”, and growing up. The canal’s towering new waterfront infrastructure, nearly identical to the kind looming over the Mission Creek, will never not be shocking to me.7 The fact that two opposite ends of this great big country could now look exactly the same is frightening, but I find solace in imagining that somewhere, like my Japan, it’s different.

Esperanto morphs fluidly, rapidly. Its (Sakamoto’s) bendy, experimental soul translates into ambient, jazz, dance music, and stuff our language still doesn’t really have a name for. It’s also not necessarily easy listening. “A WONGGA DANCE SONG”8 heads the tracklist promising a good time, and immediately reveals itself as a joyous assault on the ears, with all the power of a left hook punch, the second needle meets wax.

A side note: this album sounds good played loud, and through an iPhone speaker. Its samples almost feel like vector symbols–scalable, representational, floating points more than captured sound. Free, joyous, sensedata. Translatable, transformable. Or maybe like the way words start to sound once you’ve said them too many times. By the end of the album, I’m convinced I’m hearing the words “ULU WATU”8 spoken by the closer’s muffled synth riff. I feel like a dog hearing my name called, only half understanding.

I don’t know if the fact that Esperanto was composed for a dance of the same name makes the project make more or less sense. Here at the limits of expression, the experience clicks and unclicks, bits of words and movement at a time. It is kind of a druggy process. With each listen, my mind changes. Each time I remember, my memories are transformed, too.

Well, transformation seems lodged in Japanese cultural memory. The country’s mythos is full of shapeshifters–henge: foxes–kitsune, raccoon dogs–tanuki, even dragons–ryū. In fact, the Japanese royal family still claims direct descent from the Dragon King. Princess Zelda transforms into a dragon in 2023’s The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom.9

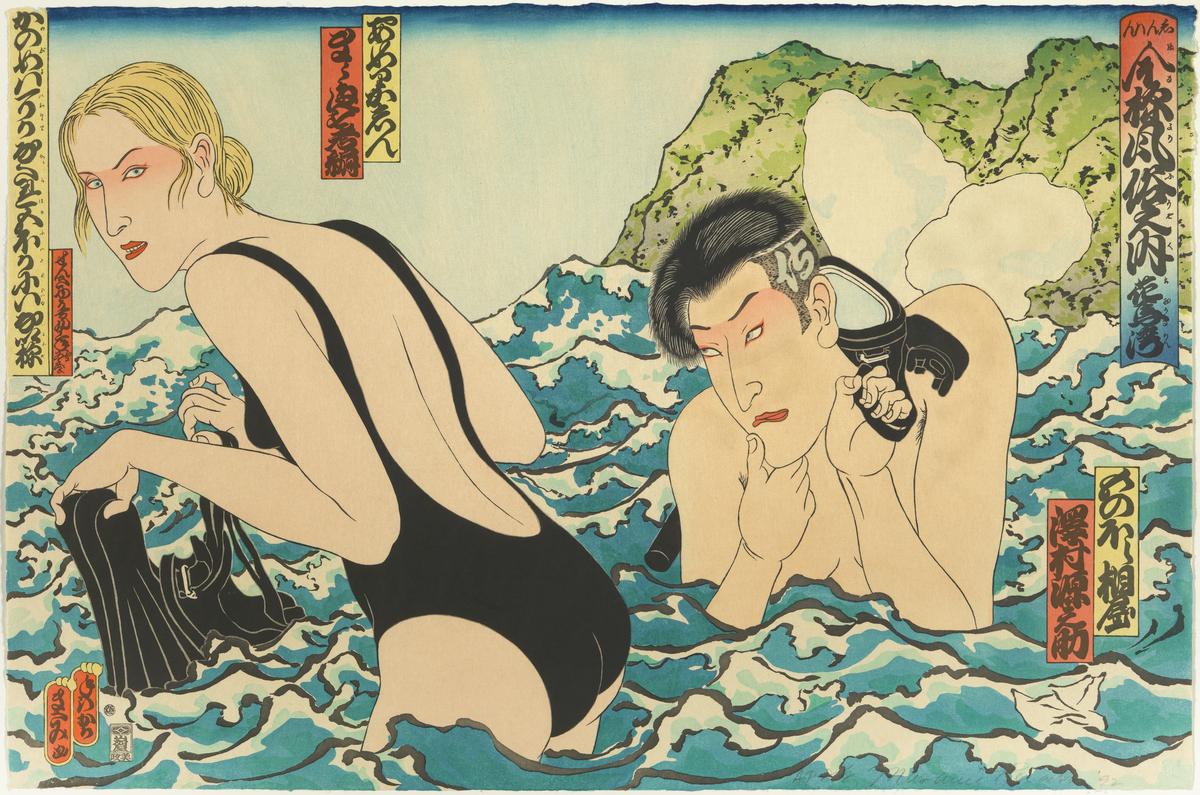

Over a hundred years ago, Japan was transformed under the Meiji Restoration, an imperial longing for the West. The restoration saw the abolition of the Tokugawa shogun’s samurai, the introduction of yen, and widespread industrialization, to name the bullet points. It’s also when Japanese elite began to dress like this:

I think it’s this characteristic restlessness to transform, and to be transformed, that’s kept me drawn to Japan. Even when it manifests itself in the guy who turned himself into a dog. It’s being game to mimic other cultures’ cues, while still belying a strangeness, something a little warped, something characteristically Japanese.

Maybe this was why, growing up, I sought out Studio Ghibli’s takes on classic western tales like Gulliver’s Travels, The Borrowers, and Earthsea, over their English language counterparts we owned on DVD. Or why, in high school, I was thrilled to learn Joe Hisaishi’s (Miyazaki’s composer)’s name is a transliteration of Quincy Jones, the Thriller producer who went to the school down the street from mine, in Seattle. Maybe I made the connection listening to Haruomi Hosono & co’s PACIFIC, feeling like the only person on the other side of the ocean who heard their music, the words to The Beach Boys’ “Girls On the Beach,” oddly familiar.

In 1978, the same year as PACIFIC, Haruomi Hosono’s breakout hit with Yellow Magic Orchestra (its own name being a take on Japaneseness) was a cover of the song “Firecracker.” This guy’s essay on the Afro Rake connection10 is remarkable, and settles on a vision of a young Afrika Bambaataa glued to the tube, watching YMO on Soul Train. Listen to Death Mix, one of the first DJs’ first sets, recorded deep in the Bronx, and hear Yellow Magic.11

It seems we’re all longing for a global language, one that can be spoken not only across space, but back and forth in time. In 1887, Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, under the name “Doktoro Esperanto”, penned Dr. Esperanto’s International Language (Unua Libro). A century later came Esperanto, the dance album. Translated into English, “Esperanto” means “one who hopes.”

We look out at the water, years ago now, and my friend tells me he used to think San Fransokyo was a real city. I laugh, and the memory fades. It’s funny, Esperanto’s not really a sad album.

Then, I’m at the end, it’s stopped playing, but the music hasn’t. I sit, smiling dumbly, hearing something entirely new dance itself out into my head. What? I blink, and I actually take out my earbuds in surprise, to confirm what I’m hearing. Music, out of chattering voices, the rolling metal of the bus, the road and the rich yellow-green earth. This melody can’t be reproduced by any feats of memory; I’ll never hear it again, yet it’ll never cease, in all the kaleidoscopic sounds of the wide world. No, no, no, I think, and the music finally fades as I’m made aware of it, fading as fast as if someone had turned a volume knob.

Keep spinning...

My Memories Fade

Ryuichi Sakamoto, 1952–2023

Why I DON'T Like Esperanto

r/WeeabooTales

The Adventures of Tadzio in Japan

Firecracker (Martin Denny)

DEATH MIX HD REMASTER!!!

Vaults of Eternity: Japan

1. Bon Iver’s If Only I Could Wait is a current favorite with a similar sound. Also hear anything produced by Ripsquad.

↩

2. See: Curiosity, Then Concern for a Dolphin in Difficulty, among others…

↩

3. Kobe, Nagoya, Nagasaki, Sapporo, Hiroshima, Saitama, Nagano… I don’t think I know the names of that many cities in any other country besides the US. Am I just projecting?

↩

4. See: Quiet Forest–moonrabbithaven.com, Wet Land–Writing About Music, Sitting with Satoshi Ashikawa’s Still Way.

↩

5. Anthony Bourdain, another great, wrote of Tokyo:

For those with restless, curious minds, fascinated by layer upon layer of things, flavors, tastes and customs, which we will never fully be able to understand, Tokyo is deliciously unknowable. I’m sure I could spend the rest of my life there, learn the language, and still die happily ignorant. ↩

6. Fluid, parallel notions connected to a greater, churning artery.

↩

7. Seriously, Google it. It’s crazy what they’ve done to one of the nastiest parts of NYC.

I canoed down the Gowanus with my dad once.

↩

8. Wangga is a genre of Aboriginal Australian music, and Uluwatu is a village in Bali. So these names are almost real words.

It’s fun to follow Ryuichi Sakamoto’s thought process. He called Esperanto “imaginary ethnic music.” Is not all music imagined, and does not all music exist the moment it’s performed?

…I get what he meant.

↩

9. Find the Triforce. ↩

10. This is such an awesome bit of music history I’m glad somebody else wrote down, and is full of revelations. One more connection I’d like to posit is that those Emori covers look an awful lot like the Big Shot guys from Cowboy Bebop… Do you see it?

↩

11. You’ll hear “Firecracker” 12 minutes in.

↩